Tết as a Way Home: Experiencing the Cultural Roots of Vietnam

20-02-2026 08:10

Main contents

Tết as a Way Home: Experiencing the Cultural Roots of Vietnam

Tết arrives, spring returns

Tết in the old days arrived slowly—like a season you could walk into. People heard Tết in the steady thud of rice pestles, smelled Tết in the woodsmoke from boiling bánh, saw Tết in freshly swept courtyards and newly cleaned ancestral altars, and counted Tết by the final market days of the year. Tết today comes faster: a bus ticket booked on a screen, greetings sent by message, a gift hamper delivered straight to the doorstep. Times are different, preparations are different, even reunion looks different—some families can manage only one meal together; some welcome Tết far from home. Yet the more you travel across regions and rhythms of life, the clearer one truth becomes: the foundation of Tết remains the “original blueprint” of Vietnamese cultural identity.

That blueprint is remarkably coherent. Tết begins with the turning of seasons—tống cựu nghinh tân (farewell to the old, welcome the new), aligning human life with the cycle of growth. It enters history as a rite that is both national and communal, marked by recorded milestones such as the Tịch Điền (Royal Ploughing Ceremony) under the Early Lê in 987, and the spring festivities within the royal court.

Tết returns to each household through cleaning and readying the home, year-end offerings, New Year’s Eve rites, and first-day ceremonies—so the living may reconnect with their ancestors, and today may rejoin its source.

And Tết spreads outward into the community through visiting, offering greetings, and mừng tuổi (New Year’s gift-giving)—to mend relationships, sow blessings, and remind one another to live a little more beautifully at the threshold of a new year.

So when we say, “Tết is for returning,” it is not merely sentimental. It is a structured cultural understanding: returning to the season and heaven’s timing, returning to household order, returning to ancestors, and returning to community—four pillars that have given Vietnamese culture its endurance through historical upheavals and modern change.

Tết in the Old Countryside

Tết in the Old Countryside

Tết as a Seasonal Threshold

Tết Nguyên Đán—the Lunar New Year—is the most sacred moment in the cycle of seasonal transition, when Âm–Dương (yin–yang) shifts and the Ngũ Hành (Five Elements) moves into harmony. It is precisely the meeting point of “Heaven’s Way” and “Human Way,” allowing Vietnamese people to tống cựu nghinh tân in step with nature’s rhythm of renewal.

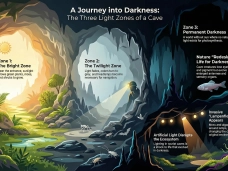

The 24 Solar Terms: the Âm–Dương Foundation

Ancient Vietnamese agricultural life followed a seasonal calendar based on the Earth’s movement, dividing the year into 24 solar terms, each about fifteen days apart, reflecting the balance of Âm and Dương.

From Đông Chí (Winter Solstice—Âm at its peak, Dương newly born), Dương energy gradually gathers. By Lập Xuân (Beginning of Spring, often around 3–5 February in the solar calendar), a crucial turning point arrives: tam dương khai thái—Dương rises, Âm descends, heaven and earth come into communion.

Lập Xuân is not Tết itself, yet Tết is always arranged to coincide with, or fall very near, Lập Xuân-when life buds and breaks ground again, and a new rice-growing cycle begins. Tết becomes a “cultural New Year’s threshold,” welcoming fresh Dương energy and sending off the cold Âm of winter.

The Five Elements at Spring’s Turning Point

Spring corresponds to Mộc (Wood): growth, sprouting, the East. Lập Xuân is when Mộc energy stirs; spring rains—Vũ Thủy (Rain Water)—begin to moisten the land (Water nourishes Wood). The elements inter-generate, completing the cycle of renewal.

According to Kinh Lễ – Nguyệt Lệnh (Book of Rites – Monthly Ordinances), the king would lead officials to the eastern gate to迎春 (welcome spring), striking an earthen ox with a five-coloured whip. In Vietnam, the Trần, Lê, and Nguyễn dynasties all maintained the Lễ Nghênh Xuân (Spring-Welcoming Rite) at the Eastern Altar, with processions of the Spring Deity and the earthen ox, praying for abundant harvests—an embodiment of Five-Element harmony.

Family Reunion during Tết

Family Reunion during Tết

Tết: Ritualising the Seasonal Turning

Yin–yang (Âm–Dương): Yin represents the quiet, cold, inward energy of winter; yang is the warm, bright, outward energy of spring. On New Year’s Eve, the old yin season is believed to give way to new yang vitality. That is why people raise the cây nêu (a tall New Year bamboo pole) to mark sacred time and ward off bad luck; why loud sounds like firecrackers traditionally “clear” negative spirits; and why lanterns and fresh blossoms are used to welcome light, warmth, and renewal.

The Five Elements (Ngũ Hành): This is a symbolic “map” of how life stays in balance through five forces—Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water. The mâm ngũ quả (five-fruit offering) represents a wish for that balanced cycle in the coming year (the exact fruits vary by region). Spring is linked with Wood—growth and sprouting—so peach/apricot blossoms and kumquat trees stand for rising life-force. Red and gold clothing suggests Fire and Earth, colours associated with warmth, prosperity, and stability—supporting the Wood energy of spring. Even the iconic pair bánh chưng (square) and bánh giầy (round) speaks in symbols: earth and sky, grounding and openness—harmony between humans, nature, and the cosmos.

In that sense, Tết is a moment of “reset”: aligning daily life with the season’s renewal, and offering prayers for peace, good harvests, and family wellbeing. The phrase “tam dương khai thái” is a traditional way of saying: the first strong rise of spring’s bright energy has begun—an auspicious start to the year.

The Origins of Tết

Tết Nguyên Đán rises from the deep roots of Vietnam’s wet-rice civilisation, tied to the 24 solar terms and the tempo of agriculture. In folk materials and historical research, from the time of the Hùng Kings (roughly 7th–3rd centuries BCE), Vietnamese communities were believed to hold New Year celebrations to thank heaven and earth and pray for abundant crops. Most iconic is the story of Lang Liêu presenting bánh chưng and bánh giầy to the sixth Hùng King. The square bánh chưng symbolises Earth; the round bánh giầy symbolises Heaven—two core images of Âm–Dương and heaven–earth harmony in Vietnamese thought. These are not merely foods, but an early cultural declaration: Vietnamese life is grounded in agriculture, centred on nature and ancestors.

“Tết,” in Sino–Vietnamese understanding, corresponds to “tiết” (a seasonal node)—a change of climate, a turning point of time. “Nguyên Đán” means “the first morning of the year.” Scholars such as Trần Văn Giáp argued that Tết existed in Vietnam from the early first century CE, well before the long centuries of Chinese rule. It is not a simple import “from China,” as some misconceptions claim, but part of a shared East Asian rice-civilisation framework—deeply localised in Vietnam, marked by ancestor worship and agrarian prayers for blessings.

The Tịch Điền Festival—originating from the Early Lê period

The Tịch Điền Festival—originating from the Early Lê period

Tết in Historical Records

Vietnamese chronicles record Tết early as both a national rite and a popular celebration. According to Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư (Complete Annals of Đại Việt), in 987 (the Đinh Hợi year, Thiên Phúc 8) under the Early Lê, King Lê Đại Hành held the first Lễ Tịch Điền (Royal Ploughing Ceremony), promoting agriculture under the principle that “agriculture is the foundation.” In 992 (Nhâm Thìn), the king “appeared at Càn Nguyên Hall to watch lanterns” to welcome spring.

Under the Lý dynasty, King Lý Nhân Tông opened the Quảng Chiếu lantern festival for seven days and nights; King Lý Thần Tông opened the Diên Quang garden for royal relatives to view flowers. By the Hồng Đức era under Lê Thánh Tông, the Nguyên Đán observance became the most important annual ceremony: officials paid court, amnesties were announced, and rites were performed to heaven and earth, and to the altars of land and grain.

An Nam chí lược by Lê Tắc (13th century) describes the New Year season from the first to the third lunar months with folk games and performances: ball games, shuttlecock kicking, swings, singing and dancing, and sacrificial rites. Under the Nguyễn dynasty, Đại Nam nhất thống chí notes that in some areas such as Xứ Đoài, Tết had once been observed in the 11th lunar month before later standardisation under a unified calendar.

European missionaries in the 17th–18th centuries, including Samuel Baron, also recorded the atmosphere of Tết in Đàng Ngoài (northern Vietnam): singing, lantern dances, cockfighting, swings—evidence of a resilient cultural life through historical turbulence.

Tết, then, is not only festivity; it is the moment when court and people alike “welcome the new year” and pray for national peace and public well-being—a tradition sustained across dynasties, confirming Tết as a cultural milestone of the nation.

The Colours of Tết

Cuisine

The Tết feast is a three-region tapestry. The North features bánh chưng, pork rolls, aspic, bamboo-shoot soup; the Central region offers bold flavours such as fermented pork rolls and fried spring rolls; the South is warmly sweet with braised pork and eggs, bánh tét, and pickled scallion heads. The five-fruit tray expresses wishes through regional choices—each fruit name and pairing carrying prayers for sufficiency, prosperity, and good fortune.

Clothing

Vietnamese people wear new clothes at Tết to “renew the self.” The áo dài, emblem of elegance and restraint, is favoured in bright auspicious tones—red, gold, pink—while avoiding sombre colours associated with mourning. Dress is not only appearance; it is respect for a sacred day.

Tết decorations—family preparations for the New Year

Tết decorations—family preparations for the New Year

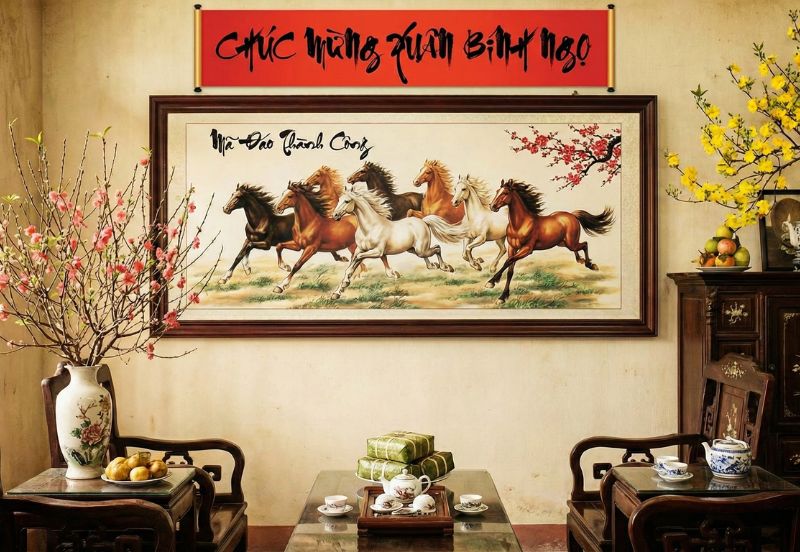

Home Decoration

Homes are cleaned thoroughly; red couplets are hung; Đông Hồ folk prints (chickens, buffalo fights, spring blessings) are pasted; the cây nêu may be raised to ward off ill fortune. Peach blossoms in the North, apricot blossoms in the South, and fruit-laden kumquat trees symbolise growth and abundance. The five-fruit tray is placed solemnly on the ancestral altar, shaping an atmosphere both warm and sacred.

Visiting and Greeting

The custom “First day: father; second day: mother; third day: teacher” expresses a moral order of gratitude. The first visitor of the year is chosen carefully to bring good fortune. A red lucky envelope given to children is not merely money; it is a blessing for peace and protection at the year’s threshold.

Ancestor Worship

This is the most sacred core. On the 30th (lunar) day, families make the year-end offering to bid farewell to the old year. At New Year’s Eve they perform rites outdoors and indoors to invite the ancestors home. On the morning of the first day, the New Year offering continues. Descendants burn incense and offer bánh chưng, candied fruits, and rice wine, praying for ancestral protection. In this worldview, “the earthly mirrors the spiritual”—ancestors still accompany their descendants.

Tết Is Not a Destination, but a Journey Home

Tết is not a destination; it is a homecoming. A return to family for reunion around a shared meal; a return to ancestors in gratitude; a return to village life and the most humane values of the nation. In today’s globalised world, as many young people live far from home, Tết becomes the thread that binds identity, the medicine of the spirit that keeps us from forgetting we are Vietnamese. As the old folk line says:

“Tháng Giêng ăn Tết ở nhà, quê hương làng xóm, ông bà tổ tiên.”

In the first lunar month, celebrate Tết at home—

with homeland, village, and ancestral grandparents.

Tết is when we pause, look back, and nourish the cultural soul to walk forward.

Through every historical rise and fall, Tết endures because it is the cultural root of the Vietnamese people—a place we can always return to, to find ourselves again. May every home enjoy a new year of peace and prosperity, and may this sacred beauty be preserved for generations to come.

Phong Việt

Comments

Comments (Total 1)

David Larry

25-02-2026

Related Articles

12-12-2025

Top 10 Best Restaurants in Phong Nha

26-11-2025

Khe Sanh – A Journey into Memory

05-11-2025

8 Unmissable Instagram Spots in Da Lat

28-10-2025