Karst Cave Formation: The Case of the Phong Nha–Ke Bang Limestone Massif

04-12-2025 10:32

Võ Văn Trí

1. Overview of karst topography and characteristics of the Phong Nha–Ke Bang limestone block

Karst is a type of landscape formed by the dissolution of soluble rocks (typically limestone and dolomite) by weakly acidic water, resulting in underground drainage systems and characteristic caves. Phong Nha–Ke Bang National Park (PNKB), located in Quang Binh Province, is one of the largest and oldest limestone massifs in Asia. The PNKB limestone belongs to the Bac Son Formation and has an age of around 400 million years (Palaeozoic), and is considered one of the oldest large-scale karst blocks in Asia.

The limestone massif covers an area of about 200,000 ha (with a core zone of 85,754 ha), in which karst topography is dominant and occupies roughly two-thirds of the World Heritage property [1]. PNKB was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2003 for its outstanding geological and geomorphological values, and again in 2015 for its biodiversity. Owing to its unique geological setting, this region contains a highly developed karst network with steep limestone mountains, tower karst, deep dolines and a complex system of underground rivers. To date, more than 400 caves of varying size have been surveyed with a total explored length of over 210–220 km [2]. Many caves in PNKB rank among the largest and most spectacular in the world, such as Phong Nha Cave, Paradise Cave (Thien Duong) and Son Doong – the largest known natural cave on the planet [3]. These exceptional geological values coupled with highly diverse ecosystems make PNKB a precious “natural geological museum” in Southeast Asia.

2. Conditions for the formation of the karst cave system in Phong Nha–Ke Bang

The development of karst caves requires the combination of multiple geological and environmental conditions. In PNKB, the necessary and sufficient factors for the formation of its vast karst cave system include:

• Geology. The PNKB massif is composed almost entirely of Carboniferous–Permian limestone (Bac Son Formation) with very high CaCO₃ purity (CaO content ~52–53%, MgO < 2%) [1]. The limestone succession is 600–1,000 m thick [1], providing a rock volume sufficiently large for deep karstification. The limestone occurs in thick beds or massive units, with many vertical cliffs and jagged summits that allow water to infiltrate to great depth. The area has been strongly affected by tectonic activity: fault systems trending mainly NE–SW, NW–SE and approximately meridional directions dissect the limestone, fracturing the rock and creating numerous joints and crushed zones [1]. This dense fracture network acts as the structural “framework” that guides karstification – water readily percolates and dissolves the limestone along these weaknesses, which are progressively enlarged into conduits and underground caves [1]. Thus, the thick, pure limestone sequence and the well-developed fault–fracture system are the fundamental geological preconditions for the formation of large-scale caves.

• Climate. Phong Nha–Ke Bang lies in a tropical monsoon climate zone, hot and humid with very high rainfall, averaging about 2,300 mm per year. Rainfall is concentrated between August and January of the following year. Abundant precipitation provides an ample water supply for limestone dissolution. As rainwater passes through the atmosphere and soil, it absorbs CO₂ to form weak carbonic acid, thereby enhancing its capacity to chemically corrode limestone. In humid tropical regions, year-round high temperatures accelerate chemical reaction rates and thus intensify rock weathering. In PNKB, the rainy season coincides with the cooler part of the year (late autumn–winter); cooler water can store more dissolved CO₂, so the efficiency of limestone dissolution increases further [1]. Overall, the hot, humid climate with heavy rainfall throughout the year in PNKB creates ideal conditions for karstification to proceed continuously and vigorously.

• Hydrology. The hydrological structure of the PNKB region is highly favourable for the development of underground rivers and caves. The Phong Nha limestone block lies at a lower elevation than surrounding areas composed of insoluble rocks, so runoff from external catchments flows towards and into the karst [1]. In practice, there is almost no significant surface flow within the PNKB limestone; rainwater and water from adjacent terrains rapidly infiltrate through karst openings and flow underground [1]. Strong subterranean flow along cave passages not only enhances chemical dissolution but also causes mechanical erosion, removing loose fragments and further enlarging underground voids. Hydrogeochemical studies show that during the rainy season the concentrations of HCO₃⁻ and Ca²⁺ in karst waters increase sharply, often tens of times higher than in the dry season, demonstrating that dissolution is particularly intense during flood periods [1]. Thus, hydrological conditions – including abundant water input and vigorous underground flow – are crucial in determining the degree of karst cave development.

• Biological factors. The dense tropical forest cover on the PNKB limestone surface not only protects the soil and maintains moisture but also provides an important source of biogenic CO₂ for rock dissolution. Rapid decomposition of organic matter in forest soils, together with respiration by plant roots and microorganisms, increases CO₂ concentrations in infiltrating water. This CO₂-rich water forms more carbonic acid when it encounters limestone, thereby accelerating calcite dissolution. In addition, biological activity (e.g. algae, mosses, bacteria) can induce biochemical corrosion on limestone surfaces and generate micro-amounts of organic acids which, although relatively minor, also contribute to the widening of small fractures. In PNKB, the limestone forest ecosystem is highly developed, with high canopy cover and thick valley soils, providing abundant CO₂ and strongly supporting karstification. In summary, biological factors – by supplying CO₂ and organic acids – constitute a key complementary condition alongside geology, climate and hydrology for the formation of the extensive karst cave system in PNKB.

Cave formation in Phong Nha - Ke Bang. Võ Văn Trí

3. Stages in the formation of karst caves

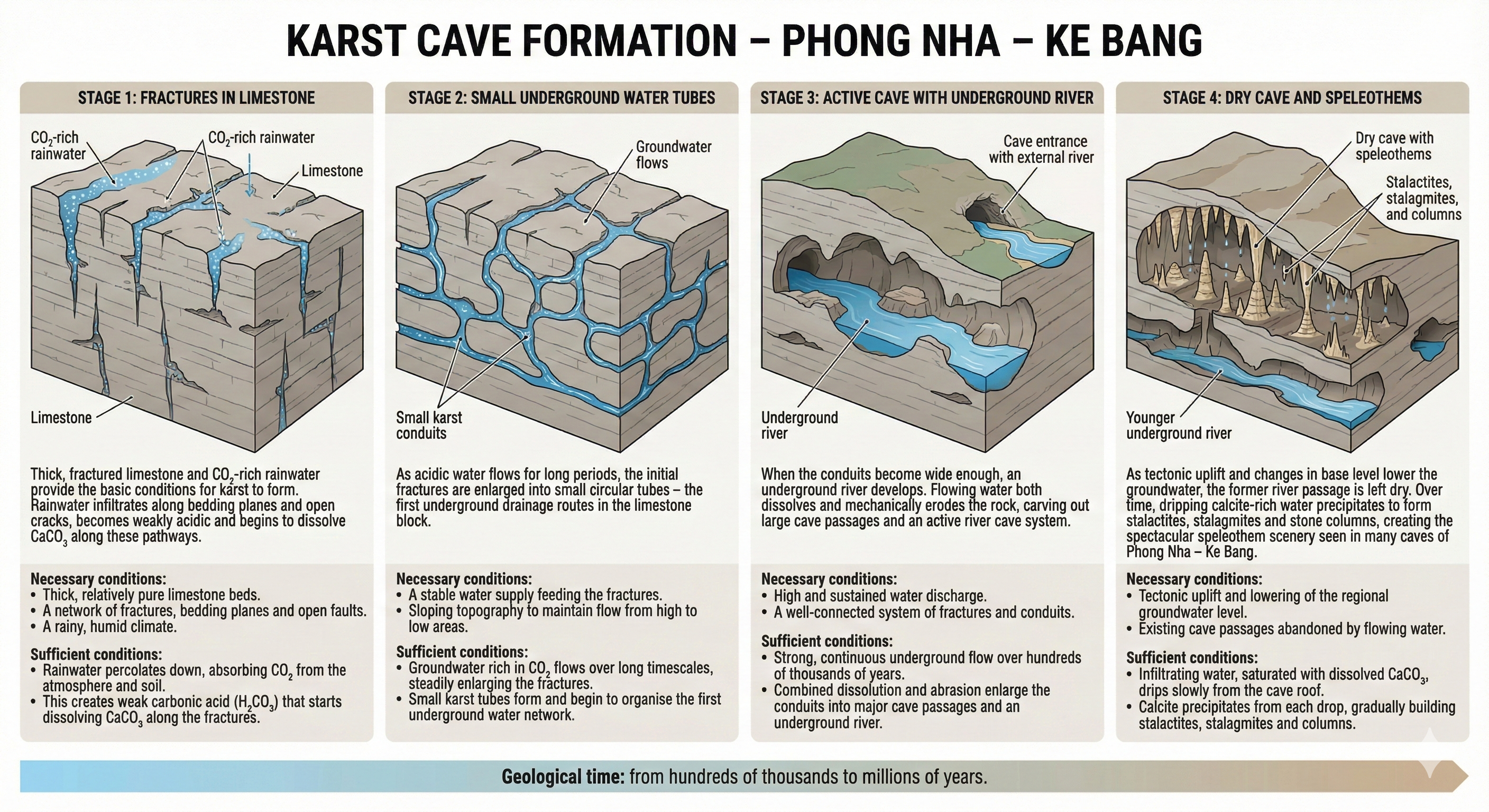

Karst caves do not form instantaneously but evolve over a prolonged time span through multiple stages. The process begins with tiny fractures in the rock and gradually develops into large fossil dry caves adorned with speleothems. A typical karst cave system in PNKB passes through the following main stages:

1) Initial fracture stage. This is the inception stage, when rainwater and surface water start to infiltrate pre-existing natural fractures in the limestone. Weakly acidic water seeps along fracture walls and gradually dissolves the limestone. Initially, dissolution is slow and widens fractures by only a few millimetres per year. However, over tens of thousands of years, fractures expand significantly in both width and depth, forming small cavities and voids within the rock. The density of fractures and the intensity of dissolution control the extent of development at this stage. In PNKB, owing to strong tectonic shattering, there are numerous fractures, so fracture enlargement occurs widely throughout the massif, resulting in a network of primitive voids – the precursors of caves.

2) Proto-conduit stage (juvenile cave development). Once fractures have widened sufficiently, water flow begins to concentrate along these underground pathways, shifting from diffuse percolation to conduit flow. At this point, small karst conduits – subsurface tunnels with cross-sections of a few centimetres to several tens of centimetres – start to form. Pressurised flow within these conduits continues to dissolve and enlarge them into larger passages. Simultaneously, fast-flowing water transports sand and gravel, causing mechanical abrasion that further widens the conduit floor and walls (the phase of mechanical “washing out”). The combination of chemical dissolution and mechanical erosion rapidly increases cave dimensions, transforming small tubes into underground passages capable of conveying subterranean streams. This stage corresponds to the formation of young water-filled caves that remain entirely underground and have not yet opened to the surface. In PNKB, early-stage conduits are often circular in cross-section, indicative of pressurised flow, and are situated deep within the massif, for example in the headwater segments of the Chay or Rao Thuong underground rivers during their initial development.

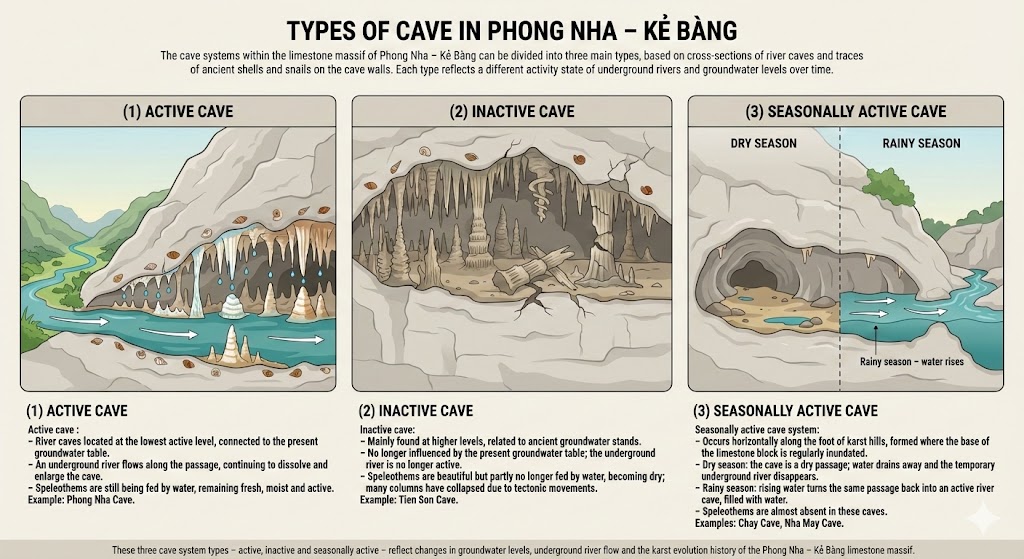

3) Development of underground rivers and mature caves. Over hundreds of thousands of years, karst conduits coalesce into the main underground river network within the karst block. Water from a wide catchment drains into this network; increased discharge continues to enlarge the caves both in length and cross-section. At maturity, large river caves form with heights and widths of tens of metres and lengths of many kilometres. The underground river meanders through the massif and typically emerges at springs where cave passages intersect hillslopes or valley sides, forming resurgence entrances. An important consequence of this stage is the establishment of the base-level drainage system of the karst. When the regional base level lowers (due to fluvial incision or tectonic uplift), the underground river adjusts to the new, lower level, leaving abandoned dry caves at higher elevations. In PNKB, many major caves were formed by ancient underground rivers. For example, present-day Phong Nha Cave is an active river cave through which the Son River flows, whereas Tien Son Cave, located ~200 m higher, is a dry cave formed by an ancient river that has long since drained away. The coexistence of this “wet–dry” cave pair clearly demonstrates a lowering of the water table and the transition from an active fluvial cave to a fossil cave.

4) Dry-cave stage and speleothem formation. When a cave is disconnected from the underground river (because the water table drops or the flow is diverted), it enters a perched dry phase. At this stage, the cave no longer conveys flowing water; only moist air and percolation water dripping from the ceiling remain. The cave atmosphere then allows mineral precipitation: dripwater saturated in Ca²⁺ and HCO₃⁻ degasses CO₂ into the cave air and precipitates calcite, forming speleothems. Over tens of thousands of years, stalactites (hanging from the ceiling) and stalagmites (rising from the floor) grow larger and may merge to form columns connecting roof and floor. Other types such as draperies, curtains and flowstones develop where water flows in thin films rather than as discrete drops. The cave thus becomes a fossil dry cave richly decorated with diverse speleothems – the final stage in the karst cave evolutionary cycle. Subsequent tectonic uplift or subsidence may open new entrances (e.g. by roof collapse) or, conversely, fill passages with sediment, bringing the cave’s evolutionary history to an end. In PNKB, Tien Son Cave, the “Dry Cave” in the Phong Nha system, and Paradise Cave are typical dry caves filled with speleothems, showing that they are stable and no longer host underground rivers. By contrast, caves still containing flowing water (such as Phong Nha and Son Doong) only have speleothems in higher parts of the cave, while river-level sections remain in an active developmental stage.

In summary, the formation of a karst cave is the result of a long-term geological evolution: from initial micro-fractures through proto-conduits and underground rivers to high-level dry caves once the water has drained away. This process may be repeated at different elevations as the landscape continues to evolve, creating multi-level cave systems superimposed within a single karst block.

4. The role of tectonics in cave development

Tectonic processes, particularly vertical crustal movements and faulting, exert a profound influence on the formation and orientation of karst caves in PNKB.

First, tectonic faults create dense fracture networks that define the principal flow paths for groundwater and thus the main directions of cave development. In PNKB, fault systems trending NE–SW, NW–SE and other directions dissect the limestone block into strongly fractured belts where the rock is highly jointed and crushed [1]. At the intersections of these fault systems, karst valleys, collapse dolines and elongated caves often form, aligned with the fault traces. Studies show that where limestone is more intensely fractured by tectonics, the density of dolines, karst shafts and caves is correspondingly higher [1]. For example, the main orientation of Phong Nha Cave coincides with the NE–SW trend of the Son Trach–Phong Nha fault zone, while the Hang Vom–Hang Doi system in PNKB also follows a deep tectonic fault. Clearly, these tectonic damage zones have guided groundwater flow and thus determined the development of long cave corridors along those structural directions.

Second, neotectonic uplift and subsidence control the formation of cave levels at different elevations. Where limestone terrain is uplifted episodically, separated by periods of relative stability, karstification tends to deepen over time: the water table lowers stepwise after each uplift phase, leaving multi-level cave systems at successively higher positions. Each cave level corresponds to a former water-table position; the higher the cave, the older it tends to be and the more likely it is to be inactive (“dead”) [1]. Studies of Vietnamese karst show that in regions of long-term tectonic uplift, as many as five cave levels can develop, from the lowest at ~0–5 m above present base level to the highest at ~150–180 m [1]. In PNKB, neotectonic uplift since the late Tertiary has contributed to the formation of cave levels; for example, Tien Son Cave at ~200 m represents an ancient level, while Phong Nha Cave (~30 m) and the present water table at lower elevations indicate that at least two cave levels have developed due to uplift. Conversely, in areas of tectonic subsidence, the water table may rise, potentially blocking and infilling lower-level caves with sediment and halting their further development [1].

In addition, tectonic uplift can cause cave-roof collapse when former phreatic roofs are raised to positions where they are no longer supported by water. This may lead to the formation of large collapse dolines that open from the surface into caves, creating skylights. PNKB hosts many collapse dolines formed by the collapse of ancient caves, notably Kong Collapse in the Tiger–Over–Pygmy cave system. Investigations show that the three caves – Tiger, Over and Pygmy – were originally parts of a single large cave; subsequent roof collapses created two huge sinkholes, segmenting the system into three separate caves with forest vegetation growing on the doline floors. The two natural skylights in Son Doong Cave are also the result of roof collapse due to uplift and extreme enlargement of the cavity. Thus, tectonic uplift not only promotes the formation of higher cave levels, but also indirectly generates collapse features that expose parts of the underground system to the surface.

In summary, tectonics acts as the “conductor” of karst cave development. Vertical motions control the distribution of cave levels in elevation, while faults determine cave orientation and plan-view morphology. The combined influence of these factors explains why PNKB contains a highly complex multi-level cave system with long, straight passages and gigantic collapse dolines – all bearing the imprint of a long tectonic history in the region.

Types of cave in Phong Nha - Ke Bang. Võ Văn Trí

Types of cave in Phong Nha - Ke Bang. Võ Văn Trí

5. Influence of the tropical humid climate on limestone weathering

The tropical humid climate of PNKB not only provides abundant water but also creates a highly aggressive chemical weathering environment that accelerates limestone karstification. Several key climatic characteristics and their implications for karst weathering can be highlighted:

• High rainfall with strong seasonality. Mean annual rainfall exceeds 2 m and is concentrated in the rainy season (from late summer to winter). During the wet season, infiltration raises the water table markedly, creating favourable conditions for widespread limestone dissolution. In contrast, the dry season lasts about six months, but relative humidity remains high, reducing evaporation and helping to maintain moisture in soils and rocks. The alternation between wet and dry seasons drives cycles of dissolution and precipitation: in the rainy season, dissolution enlarges cave passages, whereas in the dry season, the retreat of water provides space for speleothem formation. Although water is less abundant in the dry season, chemical weathering continues in karst shafts and residual pools where water persists and becomes progressively concentrated.

• High temperatures year-round. Mean annual temperatures are around 23–25 °C, with summer months exceeding 30 °C. High temperatures increase chemical reaction rates; a 10 °C rise can roughly double the rate of many chemical reactions. Consequently, in tropical regions limestone dissolves more rapidly than in cold temperate regions, where low temperatures limit reaction rates. In addition, high temperatures stimulate microbial activity, generating more CO₂ in soils (as noted in the discussion of biological factors). Overall, the hot, humid climate ensures that limestone corrosion proceeds throughout the year, unlike in cold karst regions, where dissolution is largely confined to the warm season.

• CO₂-rich and organic-acid-rich waters. Humid tropical forest ecosystems provide a large quantity of decomposing organic matter. Infiltrating soil water under such forests accumulates CO₂ (from plant roots and microbes) and organic acids such as humic and fulvic acids derived from leaf litter. When such water flows into limestone, it produces much stronger chemical corrosion than pure rainwater. Experimental data show that forest soil waters in tropical regions have lower pH (are more acidic) and higher dissolved ion concentrations than waters in sparsely vegetated areas. In PNKB, this factor helps to create a variety of small-scale karst features, such as sharp karren grooves on exposed limestone surfaces (locally known as “cat-ear rock”) produced by acidic runoff, and thick red weathering mantles formed where soluble minerals have been removed, leaving residual iron oxides and clays.

• Karst floods and mechanical erosion. The PNKB climate is characterised by intense, short-duration rainstorms that generate flash floods. Karst floods rise rapidly within underground rivers and then drain quickly through karst outlets, creating powerful erosive forces. Evidence from the historic 2010 flood shows that floodwaters carved new “hanging pools” in Phong Nha Cave by scour, which then drained to leave perched basins. One such perched pool, with an area of about 500 m², lies partway up the cave wall, ~30 m above the active underground river, providing striking evidence of the impact of karst floods in a tropical humid climate. Floods also flush out sediment, “cleaning” cave floors and keeping passages open rather than allowing them to be infilled; however, extreme floods may destroy speleothems or cause collapse in structurally weak sections of caves.

Taken together, the tropical humid climate is both a “driving force” and a “test” for PNKB karst. It supplies the water and thermal energy for intense karstification (limestone corrosion rates in the tropics may reach millimetres per year, much higher than in cold or arid regions). At the same time, climatic extremes such as severe floods create distinctive geomorphic features (collapse dolines, hanging pools, etc.) within the PNKB cave systems. Without the hot, humid climate, PNKB would be unlikely to possess the spectacular, multi-level and dynamic cave networks observed today.

6. Multi-level cave topography in Phong Nha–Ke Bang – representative examples

As a result of the combined effects of geology, tectonics and climate, the Phong Nha–Ke Bang karst massif exhibits a remarkably complex multi-level cave topography. This means that within a single limestone block, caves occur at a range of elevations, recording the evolutionary history of karst through different geological periods. Some representative examples include:

• The Phong Nha–Tien Son wet–dry cave pair. Phong Nha Cave and Tien Son Cave are located close to one another but at markedly different elevations, forming a textbook example of multi-level cave morphology. Phong Nha Cave lies at an elevation of only ~40 m (its entrance is at the Son River), with an underground river of ~14 km flowing through the mountain. In contrast, Tien Son Cave (also known as the Dry Cave) lies high on the cliff at ~200 m above the river, about 100 m south of the Phong Nha entrance. Tien Son is ~1 km long, completely dry, richly decorated with speleothems and has no hydrological connection with the Phong Nha river passage below. Researchers interpret Tien Son as the fossil upper level of the Phong Nha system, formed millions of years ago by a high-level underground river, after which the water table dropped and flow switched to the lower level, creating present-day Phong Nha Cave. The coexistence of Phong Nha (an active river cave) and Tien Son (a fossil dry cave) is compelling evidence of two generations of cave development stacked vertically, resulting from tectonic uplift and progressive lowering of the water table.

• The multi-level Son Doong–Hang En cave system. Son Doong Cave is currently regarded as the largest known cave in the world, with heights of up to ~200 m, widths of ~150 m and a length of nearly 5 km. Son Doong connects with Hang En (another large cave), forming part of the Vom cave system. A striking feature of Son Doong is the presence of two gigantic roof collapses, or skylights, that admit sunlight deep into the cave and support dense forests on the doline floors. Studies indicate that Son Doong was once a completely enclosed underground river cave; as the cave enlarged and the region was uplifted, the roof collapsed at structurally weak points, creating the present skylights. This reflects a transition from a fully subterranean cave to a partially open cave with collapsed roofs – an intermediate stage in multi-level karst evolution. Furthermore, the Son Doong–Hang En system displays vertical hydrogeological zoning: Hang En represents an upstream segment at a higher level; water flows through Son Doong and then sinks again to a lower level to emerge via another cave. This complex, multi-tier structure reflects long-term karst development through several cycles of water-table lowering.

• The Tiger–Over–Pygmy collapse-cave chain. This is a distinctive cave system recently explored in PNKB, illustrating multi-stage cave development and segmented collapse. The system comprises three large caves – Hang Ho (Tiger), Hang Over and Hang Pygmy – located deep within the PNKB core zone. Surveys indicate that they were originally interconnected as a single continuous cave; later, roof collapse created two large dolines, dividing it into three discrete segments. At present, the exit of Hang Ho leads to Hang Over via a ~125 m deep collapse doline (named “Massive Attack”), and from Hang Over another doline provides access to Hang Pygmy. Pygmy Cave is now ranked as the world’s fourth largest cave entrance (with a roof height of ~100 m), reflecting its origin as the terminal part of a large ancestral cave. The Tiger system demonstrates that strong karstification combined with tectonic uplift has produced the spectacular geomorphology of “multi-level caves linked by collapse dolines”. Within these dolines, light and rainfall support cave-forest ecosystems with trees, birds and bats – a striking ecological feature of multi-level caves.

• “Ky Lake” – a hanging pool in Phong Nha Cave. Recently, Vietnamese explorers discovered a perched underground pool high within Phong Nha Cave, described as a “strange lake” because of its unusual position. This pool has an area of ~500 m² and lies on a ledge some 30 m above the Phong Nha underground river and ~10 m above Xuyen Son Lake, a smaller pool (70 m²) below. The existence of this “hanging lake” indicates that a high-level passage parallel to the main river passage is present within Phong Nha Cave, likely formed by eddying floodwaters that scoured out a depression and then retreated, leaving residual water. Researchers infer that numerous major floods over geological time sculpted this perched basin – a remnant of a former high water level in the cave. Together with the skylights in Son Doong, this feature shows that the Phong Nha system preserves several relict groundwater levels and semi-inundated passages at different elevations, further enriching the multi-level karst architecture of PNKB.

These examples confirm that the Phong Nha–Ke Bang karst terrain has a highly complex three-dimensional structure with multiple superimposed cave levels. Each level corresponds to a distinct phase of karst development under specific conditions. This vertical complexity enhances the scientific value of the area (as a record of geological evolution preserved in “archives” of cave levels) and creates unique and spectacular landscapes. Few places in the world, like PNKB, allow visitors to travel by boat through a low-level underground river, then climb to a high-level dry cave rich in speleothems, or descend into collapse dolines to experience sunlit forest ecosystems within vast caverns. This is powerful evidence of intense, long-lasting karstification under the combined influence of tectonics and climate in the Phong Nha limestone mountains.

Entrance of Phong Nha Cave. PNKB

Entrance of Phong Nha Cave. PNKB

7. Research on karstification processes in Phong Nha–Ke Bang

With its unique characteristics and outstanding scale, the PNKB region has long attracted both national and international scientific research on karst geology and cave formation.

Even before its inscription as a World Heritage site, Vietnamese geologists had already investigated PNKB karst. In 1991–1992, Dang Ngoc Thanh and colleagues surveyed the PNKB caves to compile geological documentation for the designation of the national park (providing the basis for subsequent UNESCO recognition). These foundational studies established that the PNKB block consists of thick Devonian–Carboniferous limestone, strongly faulted and karstified in multiple stages. Nguyen Thi Ngoc Yen and Nguyen Duc Ly (Department of Science and Technology of Quang Binh) conducted in-depth analyses of the natural factors influencing PNKB karst, emphasising the roles of fault structures, humid climate and the interaction between karst and non-karst terrain in the region [1]. Their work clarified why karst in PNKB is more strongly developed, complex and diverse than in many other parts of Viet Nam.

From the perspective of karst hydrology, Do Quang Thien et al. (2011) examined karst activity in the PNKB limestone using a hydrogeochemical approach [3]. By analysing the chemical composition of water from many caves, they assessed the current intensity of karst processes. Their results showed that PNKB groundwater has high hardness and elevated dissolved ion concentrations with strong seasonal variability, indicating that limestone dissolution is highly sensitive to the rainy season and may contribute to subsidence and cave-roof collapse hazards. The study also proposed regular monitoring of karst water quality to evaluate the stability of the PNKB World Heritage property in the context of tourism development [3].

At the scale of individual caves, numerous national projects have focused on representative sites. For example, Dang Van Bai and Nguyen Xuan Nam (2005) conducted field investigations in the Phong Nha–Tien Son caves, clarifying the relationships between cave levels as described above. Tran Nghi (2010) surveyed Paradise Cave shortly after its discovery, recognising it as a model of a high-level dry cave with monumental speleothem formations. More recently, Mai Thanh Tan et al. (2024) published a study on paleokarst in PNKB and Hin Nam No (Lao PDR) – that is, ancient karst features buried within the rock – thereby confirming that the region underwent intense karstification hundreds of millions of years ago, leaving relict karst deposits preserved in caves [4]. This represents a new research direction that enhances our understanding of the long-term geological evolution of the area.

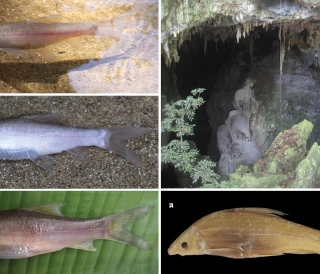

Regarding cave exploration, the British Cave Research Association (BCRA) has made major contributions. Since 1990, British–Vietnamese expeditions have surveyed most of the major caves in PNKB, discovering more than 300 new caves. A landmark achievement came in 2009, when a Royal British expedition discovered and surveyed Son Doong Cave, which was subsequently recognised as the world’s largest cave [5]. The results of PNKB cave exploration have been published internationally (e.g. in Cave and Karst Science and National Geographic, 2011), attracting global attention and stimulating interest among earth scientists. Thanks to these efforts, approximately 30% of the PNKB area has now been surveyed for caves, with a total explored length of ~250 km, and many rare cave-dwelling species (blind fish, endemic invertebrates, etc.) have been discovered.

International organisations such as UNESCO and IUCN also participate in research and conservation advisory work on PNKB karst. The UNESCO (2015) report recognises PNKB as a model of tropical humid karst that has evolved continuously from the Palaeozoic to the present day [2]. IUCN has recommended strengthening Viet Nam–Lao cooperation to study PNKB and Hin Nam No as a single transboundary karst system. PNKB is also being used as a natural laboratory for climate-change research (using speleothems as archives of past climate) and for studying karst geomorphology in tropical environments.

In conclusion, karstification processes in Phong Nha–Ke Bang are being studied comprehensively across multiple disciplines, including geology, hydrology, ecology and archaeology. Collaboration between Vietnamese and international scientists has partly unravelled the history of formation of this unique cave system and has provided important recommendations for conservation and sustainable development of the heritage. PNKB is not only a natural treasure of Viet Nam but also one of the world’s most dynamic “living laboratories” for the study of tropical karst and caves.

References

-

Do Quang Thien, Nguyen Thi Ngoc Yen, Vu Cao Minh (2011). “Karst activity of the Phong Nha–Ke Bang limestone massif from a hydrogeochemical perspective.” Journal of Earth Sciences, 33(4), 669–673.

-

UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2023). “Phong Nha–Ke Bang National Park and Hin Nam No National Park” – World Heritage List description.

-

Nguyen Thi Ngoc Yen, Nguyen Duc Ly (201x). “Analysis of the causes and conditions for the initiation and development of karst in the Phong Nha–Ke Bang limestone massif, Quang Binh.” Scientific report, Department of Science and Technology of Quang Binh.

-

M. T. Tan, V. T. M. Nguyet, H. V. Tha, B. V. Thom, L. T. Phuc, and L. T. Tuat, “Paleokarst in Phong Nha–Ke Bang–Hin Nam No and its geomorphological and geological values,” VNU Journal of Science: Earth and Environmental Sciences, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 72–91, 2024, doi: 10.25073/2588-1094/vnuees.5065.

-

Tran Nguy (ed.), Howard Limbert (eds.) (2014). Phong Nha–Ke Bang: A World Karst Wonder. The Gioi Publishers, Ha Noi. (Compilation of PNKB cave explorations by the Royal British expedition and related karst studies).

Thế giới động vật hang động Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng

Khám phá thế giới động vật hang động Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng: cá mù Hang Va, tôm càng Phong Nha, bọ cạp Thiên Đường, ốc nón Sơn Đoòng và các loài mới cho khoa học trong karst.

Đặc điểm và giá trị toàn cầu của hệ thống hang động karst Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng

Phong Nha - Kẻ Bàng có tuổi karst cổ, cấu trúc nhiều hệ thống hang lớn, phân tầng và hình thái đa dạng của Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng, đối chiếu với các di sản hang động tiêu biểu thế giới.

Hệ Thống Cảnh Báo Sớm: Lá Chắn Mềm Trước Thiên Tai

Trong bối cảnh khí hậu toàn cầu ngày càng nóng lên và các hiện tượng thời tiết cực đoan gia tăng, thiên tai ở Việt Nam đang gây thiệt hại nặng nề về người và tài sản. Bài viết phân tích vai trò của hệ thống cảnh báo sớm thiên tai như một “lá chắn mềm” giúp giảm nhẹ rủi ro

Chân Linh và Phong Nha – Mối liên hệ địa danh học, văn hiến học và địa tầng tên gọi cổ

Bài viết về Động Chân Linh và động Phong Nha trong hệ thống địa danh học và văn hiến học Việt Nam, từ thế kỷ XVI đến đầu thế kỷ XX. Dựa trên các nguồn như Ô Châu Cận Lục, Đại Nam Nhất Thống Chí, Phủ Biên Tạp Lục, kết hợp khảo cổ học và ý nghĩa Hán tự