Phong Nha Paleontology – Evolutionary Evidence of Earth’s History

19-09-2025 15:15

Main contents

1. Introduction

Vietnam possesses a long and complex geological history, recorded through multiple tectonic and sedimentary phases. Across the country, the oldest strata bearing fossils range from the Cambrian–Ordovician to younger Cenozoic deposits, reflecting the biodiversity shifts over geological time. In particular, the Phong Nha – Ke Bang area (Quang Binh Province) stands out for its very early geological foundation; research indicates that the region has experienced a continuous evolutionary history since the Ordovician (~460 million years ago) up to the present [1]. The entire Phong Nha massif is a vast Paleozoic limestone block—considered the largest classic tropical humid karst formation in Asia, and possibly one of the most significant and long-lived karst systems on Earth [1]. This enduring Paleozoic limestone bedrock has given rise to an extensive karst landscape with highly diverse geomorphology and cave systems. Phong Nha – Ke Bang National Park today is home to more than 400 known caves, formed within limestone hundreds of millions of years old [1]. The prolonged karst processes have preserved valuable records of ancient life embedded within the rock.

In 2003, UNESCO inscribed Phong Nha – Ke Bang National Park as a World Natural Heritage Site under criterion (viii) for geology and geomorphology, stating that the property “is an outstanding example representing major stages of Earth’s history, including the record of life (paleontology), ongoing geological processes, and distinctive geomorphic features” [2]. This recognition affirms the global significance of the park’s geological and paleontological heritage. Within this context, paleontological research in Phong Nha – Ke Bang is not only crucial for reconstructing the evolutionary geo-biological history of the region, but also contributes to enriching the “record of life” within the World Heritage dossier, while supporting education and scientific tourism.

2. Representative Paleontological Evidence in Phong Nha

Phong Nha – Ke Bang is often regarded as an “open-air geological museum,” hosting a wide variety of fossils distributed both on exposed rock cliffs and within deep caves. Below are some representative paleontological records that have been and are still being studied in this region:

Corals and ancient reef organisms (Middle Devonian):

At the Ruc Cay Da site (Xuan Hoa Commune, Minh Hoa District), scientists have discovered a fossil coral reef dating back approximately 350 million years (Middle Devonian) [1]. The limestone of the Muc Bai Formation (Givetian stage, Middle Devonian) here contains an abundance of fossilized corals and reef-building organisms, especially stromatoporoids [1]. These remains represent an ancient shallow-marine tropical coral reef, with a remarkable level of preservation and fossil richness rarely found elsewhere in Vietnam [1].

Typical fossils collected include corals such as Thamnopora, Alveolites, Scoliopora, as well as brachiopods (Stringocephalus, Desquamatia, Gypidula, Schizophoria, etc.), which are characteristic of the Givetian stage [1]. The high concentration of corals and brachiopods at Ruc Cay Da surpasses that of other coeval limestone areas in Vietnam (e.g., Trung Khanh – Cao Bang, Kinh Mon – Hai Duong). This highlights Ruc Cay Da as a unique paleontological heritage site, providing strong evidence for the flourishing development of tropical coral reef ecosystems during the Middle Devonian [1].

Cave Wall Preserving Ancient Fossilized Organisms – Phong Nha Karst

Cave Wall Preserving Ancient Fossilized Organisms – Phong Nha Karst

Dense Brachiopod Fossils:

Along the Nan River (Minh Hoa District), researchers have documented an outcrop of the Muc Bai Formation exposing argillaceous limestone beds densely packed with brachiopod fossils [1]. Over a rock face stretching about 20 meters, thousands of ancient brachiopod shells are tightly clustered together. The fossil density at this site is considered unprecedented in Vietnam—even surpassing the well-known brachiopod fossil site at Ma Le (Dong Van Karst Plateau) [1].

The brachiopod fossils collected here include numerous characteristic Middle Devonian genera and species such as Stringocephalus sp., Desquamatia sp., and Gypidula biplicata [1]. These specimens provide valuable material for taxonomic studies of brachiopods and contribute important insights into the reconstruction of ancient marine environments [1].

Brachiopod Fossil – Devonian Brachiopod Evidence in Phong Nha

Brachiopod Fossil – Devonian Brachiopod Evidence in Phong Nha

Conodont Fossils and the Late Devonian F/F Boundary:

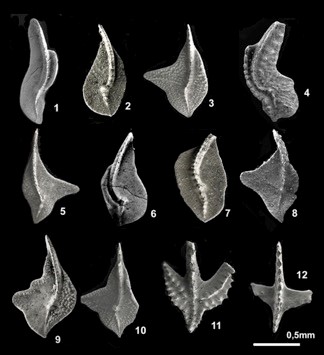

The Xom Nha section (Minh Hoa District) is renowned for preserving the boundary between the Frasnian and Famennian (F/F) stages of the Late Devonian. Within the gray limestone beds of the Xom Nha Formation, abundant conodont fossils—“teeth” of extinct primitive vertebrates—have been discovered [1].

Characteristic species of the genus Palmatolepis (e.g., P. triangularis, P. linguiformis, P. glabra), along with representatives of Polygnathus, Icriodus, and Hindeodella, have been identified in these Devonian–Carboniferous transitional strata [1][3]. Based on the appearance and disappearance of key index taxa, Prof. Ta Hoa Phuong and colleagues precisely determined the position of the F/F extinction boundary within the stratigraphic column at Xom Nha [3].

This discovery not only records the end-Devonian extinction event in Vietnam’s geological archive but also enriches regional and global comparative studies of one of the most significant biotic crises in Earth’s history.

Conodont Fossil – Devonian Microfossil Evidence in Phong Nha

Conodont Fossil – Devonian Microfossil Evidence in Phong Nha

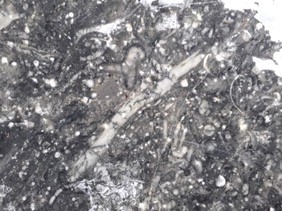

Foraminiferal Fossils in Carboniferous Deposits:

At the geological section located at kilometer 5 on the Quy Dat – Dong Le road (Minh Hoa District), geologists identified evidence of turbidite-type sedimentary structures within limestones dated to approximately 300 million years ago (Carboniferous) [1]. This represents the first recorded occurrence of turbidite structures in carbonate deposits of central Vietnam [1].

Remarkably, the limestone samples contain a diverse assemblage of deep-water foraminifera from the Visean stage (Early Carboniferous). The identified genera include Brunsia, Endothyra, Archaediscus, Tetrataxis, Endostaffella, Planoarchaediscus, and Palaeotextularia, which are characteristic of the Visean (ca. 345–330 Ma) [1].

The presence of these foraminiferal communities indicates that the depositional environment was a relatively enclosed shallow basin or inland sea during the Early Carboniferous. These findings provide valuable insights into the palaeoenvironmental conditions and stratigraphic framework of the Carboniferous–Permian record at Phong Nha.

Foraminifera Fossil – Paleozoic Microfossil Evidence in Phong Nha

Foraminifera Fossil – Paleozoic Microfossil Evidence in Phong Nha

Cave Fossils (Cenozoic):

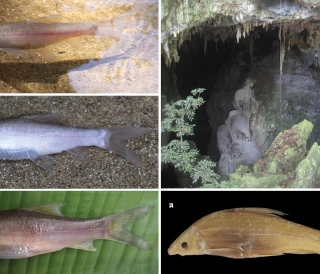

Not only on the surface, but many of Phong Nha’s vast caves also preserve remarkable fossil records. In Son Doong Cave (within the Bac Son Formation limestones, dated to the Carboniferous–Permian), two particularly significant fossil discoveries have been made.

First, a massive fossil coral block is embedded in both the wall and floor of the cave. This coral belongs to the Rugose corals (family Dibunophyllidae), remnants of an ancient reef that once thrived in a shallow tropical sea [1]. It is considered the largest and most visually striking cave coral fossil ever found in Vietnam, far surpassing the fossil coral previously discovered in Dong Doi Cave [1].

Second, near the far end of Son Doong Cave, explorers uncovered a nearly intact skeleton of a hoofed mammal (Euungulata) preserved in travertine deposits. Measuring about 2 meters in length and lacking only the skull, the fossilized remains have been mineralized and firmly cemented into the limestone floor, ensuring exceptional preservation [1]. According to archaeologist Dr. Vu The Long, the specimen likely belonged to an ancient ungulate species, possibly related to deer or mountain goats [1]. Such large-mammal fossils in dry caves are extremely rare and provide valuable evidence for studying faunal communities of the Late Quaternary (Holocene–Pleistocene) in the Phong Nha region.

In addition, the walls of caves such as Phong Nha and Son Doong display abundant marine fossils—including corals, crinoids, gastropods, and bivalves—exposed by underground river erosion. Together, they form a striking “fossil corridor,” a natural gallery of marine life over 300 million years old, bearing witness to the time when Phong Nha was once a shallow tropical sea teeming with biodiversity.

Four-Rayed Coral Fossil – Paleozoic Coral Evidence in Phong Nha

The paleontological evidence described above spans a wide range of fossil groups and distribution sites—from surface outcrops (such as Ruc Cay Da, Xom Nha, and Quy Dat) to the depths of caves (Phong Nha, Son Doong, etc.). These records provide direct testimony to the existence of life during different stages of Earth’s history, while also reflecting environmental fluctuations across long geological cycles.

3. Geological Ages of Phong Nha Fossils

Fossils in Phong Nha–Ke Bang span multiple geological periods, providing crucial evidence for dating rock formations and reconstructing the region’s geological evolution. Based on paleontological studies, the main fossil ages in Phong Nha can be summarized as follows:

-

Late Ordovician – Early Silurian (~450–420 million years ago):

The oldest record in Phong Nha is associated with clastic sediments of the Long Dai Formation. Black shale layers of this unit contain fossilized graptolites (Graptolithina), a key index group for the Ordovician–Silurian transition [1]. The presence of these fossils indicates that Phong Nha was once submerged under deep marine conditions at the end of the Ordovician. -

Middle Devonian (~390–380 million years ago):

The Muc Bai Formation (Givetian Stage, Middle Devonian) hosts abundant fossil corals and brachiopods. Corals such as Thamnopora and brachiopods like Stringocephalus burtini confirm the Givetian age of this unit [1]. This reflects a shallow tropical marine environment favorable for reef growth and rich marine biodiversity. -

Late Devonian (~372–359 million years ago):

The Xom Nha section captures the transition from the Devonian to the Carboniferous. Conodont fossils from the latest Devonian (Palmatolepis triangularis, P. linguiformis, etc.) and earliest Carboniferous species allow geologists to pinpoint the Frasnian–Famennian (F/F) boundary, marking a global mass extinction event around 372 Ma [3]. Thus, the Late Devonian record in Phong Nha is directly tied to one of Earth’s major biotic crises. -

Early to Middle Carboniferous (~359–323 million years ago):

Fossil foraminifera of the Visean stage discovered in the Phong Nha Formation provide evidence of early Carboniferous marine sediments in the region. Genera such as Endothyra, Archaediscus, Tetrataxis confirm a Visean age [1]. In addition, the Bac Son Formation (Late Carboniferous–Early Permian) contains four-rayed corals and crinoids preserved in caves, indicating limestone deposition from the late Carboniferous into the early Permian (ca. 300–250 Ma) [4]. -

Permian (~299–252 million years ago):

This stage is represented by the Bac Son limestone, which forms the dominant bedrock of the Phong Nha massif. Fossil corals and crinoids (>300 Ma) in Son Doong Cave likely belong to the Late Carboniferous or Early Permian. After the Permian, the region was uplifted during the Indosinian orogeny, leaving no trace of overlying Mesozoic marine sediments. Consequently, Triassic and Jurassic fossils are absent in the Phong Nha limestone. -

Quaternary (last 2.6 million years):

Cave sediments and fossil remains document the Quaternary, primarily the Holocene. A nearly complete fossil skeleton of an ungulate (likely deer or wild goat) in Son Doong Cave is estimated to date back several thousand years, possibly Holocene in age, preserved through natural calcification [1]. Additionally, fossilized mollusk shells and fish bones found in dry-cave sediments indicate faunal presence during the Pleistocene–Holocene, linked to recent glacial–interglacial cycles.

In summary, the fossil record of Phong Nha spans from the Early Paleozoic (Ordovician) to the Quaternary. This broad chronological spectrum reflects the fact that Phong Nha–Ke Bang has preserved nearly all major stages in Earth’s evolutionary history, serving as a priceless “fossil archive” within the World Heritage landscape.

4. Scientific Significance of Phong Nha’s Paleontological Heritage

The paleontological discoveries in Phong Nha–Ke Bang carry profound scientific significance in multiple aspects:

Recording the history of life’s evolution:

The fossils preserved here serve as concrete evidence of biological evolution across geological eras. For example, the Middle Devonian coral reef at Ruc Cay Da illustrates the explosion of marine invertebrate diversity during the Devonian [1]. The presence of the Late Devonian F/F extinction boundary at Xom Nha allows detailed study of one of the most significant biotic crises in Earth’s history [1][3]. With a fossil sequence spanning from the Paleozoic to the Quaternary, Phong Nha–Ke Bang acts as a “stone chronicle” reflecting the rise and decline of life forms and environmental changes across hundreds of millions of years.

Stratigraphic dating and geological correlation:

Fossils are vital tools for relative dating of sediments. The discovery of index fossils (e.g., Givetian corals and brachiopods, conodonts marking the F/F boundary, Visean foraminifera) has enabled precise dating of formations such as Long Dai, Muc Bai, Xom Nha, Phong Nha, and Bac Son [1]. This provides geologists with a solid basis for correlating limestone strata of Phong Nha with other regions worldwide. For instance, the presence of foraminifera genera such as Endothyra and Archaediscus at Quy Dat confirms equivalence with the globally recognized Visean stage (Early Carboniferous) [1]. Such correlations are crucial for reconstructing regional geological history, including marine transgressions, regressions, and tectonic activity.

Reconstructing paleogeography and paleoenvironment:

Through paleontological evidence, scientists can infer ancient environments. Middle Devonian corals and stromatoporoids indicate that Phong Nha was once a shallow tropical sea suitable for reef development [1]. In contrast, deep-water foraminifera assemblages from Quy Dat suggest restricted marine basins during the Early Carboniferous [1]. The absence of Mesozoic marine fossils and the development of karst topography reveal that, after the Permian, the area was uplifted into land. During the Quaternary, the discovery of a large ungulate skeleton in Son Doong Cave reflects the presence of tropical forest fauna and unique geomorphological conditions (collapse dolines opening into caves) in the Holocene. These paleoenvironmental records shed light on the long-term processes shaping Phong Nha’s distinctive karst landscape.

Contribution to heritage records and science education:

The paleontological heritage of Phong Nha–Ke Bang holds exceptional value not only for science but also for education and tourism. UNESCO’s recognition of Phong Nha under Criterion (viii) for geology and geomorphology is partly based on these significant paleontological records, which demonstrate “major stages of Earth’s history” [2]. Today, fossil localities such as the Ruc Cay Da coral reef and the Xom Nha section serve as “natural laboratories” for research and student training [1]. If conserved and properly interpreted, they can also become unique geo-tourism attractions. For example, the dense brachiopod fossil wall along the Nan River could be developed into an educational science trail, allowing visitors and students to observe fossils hundreds of millions of years old in situ [1]. In fact, the exposed coral fossils along the “fossil corridor” of Son Doong Cave already astonish explorers visiting the world’s largest cave [4].

Thus, the scientific value of Phong Nha’s paleontology goes hand in hand with its educational and aesthetic significance, contributing to raising public awareness of geological heritage conservation.

5. Conclusion

With a geological history that has developed continuously since the Early Paleozoic and a karst system evolving over hundreds of millions of years, Phong Nha–Ke Bang has preserved invaluable paleontological evidence that reflects Earth’s long evolutionary journey. From Ordovician–Silurian marine fossils, Devonian coral reefs, and traces of the Late Devonian mass extinction, to Carboniferous–Permian marine remains and Quaternary vertebrate fossils, each discovery in Phong Nha represents a vital piece of the grand narrative of Earth’s past. These records not only affirm Phong Nha–Ke Bang’s global significance in geological and paleontological research—as recognized by UNESCO in 2003 under Criterion (viii) for geology and geomorphology [2]—but also enrich Vietnam’s natural heritage.

Looking ahead, continued research and conservation of Phong Nha’s paleontological heritage are essential. Every fossil and stratigraphic section here is a unique archive, enabling present and future generations to better understand the origins and evolution of life on our planet. As a true “geological witness”, Phong Nha–Ke Bang will continue to tell fascinating stories of Earth’s history, inspiring scientists and nature enthusiasts worldwide.

References

[1] T. H. Phương (chủ biên), Báo cáo tổng kết đề tài KHCN “Nghiên cứu, đánh giá những giá trị địa di sản nổi bật, ngoại hạng của Vườn Quốc gia Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng nhằm đẩy mạnh phát triển du lịch”, Quảng Bình, 2023.

[2] UNESCO World Heritage Centre, “Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park,” hồ sơ Di sản thiên nhiên thế giới, 2003.

[3] L. T. P. Lan, B. B. Ellwood, và T. H. Phương, “Xác định ranh giới F/F trên các hệ tầng đá vôi tại Xóm Nha, Quảng Bình bằng phương pháp MSEC,” Vietnam Journal of Earth Sciences, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 30–37, 2007.

Thế giới động vật hang động Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng

Khám phá thế giới động vật hang động Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng: cá mù Hang Va, tôm càng Phong Nha, bọ cạp Thiên Đường, ốc nón Sơn Đoòng và các loài mới cho khoa học trong karst.

Đặc điểm và giá trị toàn cầu của hệ thống hang động karst Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng

Phong Nha - Kẻ Bàng có tuổi karst cổ, cấu trúc nhiều hệ thống hang lớn, phân tầng và hình thái đa dạng của Phong Nha – Kẻ Bàng, đối chiếu với các di sản hang động tiêu biểu thế giới.

Karst Cave Formation: The Case of the Phong Nha–Ke Bang Limestone Massif

This article explores the karst cave formation process in the Phong Nha – Ke Bang limestone massif, highlighting geological stages shaped by water, tectonics, and tropical climate over millions of years.

Hệ Thống Cảnh Báo Sớm: Lá Chắn Mềm Trước Thiên Tai

Trong bối cảnh khí hậu toàn cầu ngày càng nóng lên và các hiện tượng thời tiết cực đoan gia tăng, thiên tai ở Việt Nam đang gây thiệt hại nặng nề về người và tài sản. Bài viết phân tích vai trò của hệ thống cảnh báo sớm thiên tai như một “lá chắn mềm” giúp giảm nhẹ rủi ro